The official language of Jamaica is Standard Jamaican English. Children learn to speak Standard Jamaican English in schools from a very young age and are told to speak it at all times since it is generally considered to be the language that grants individuals access to a higher socioeconomic status in Jamaica. It is generally the language used in businesses, schools, churches, and the mass media. However, most Jamaicans speak Jamaican Creole as their first (or native) language which is considered to be grammatically incorrect, “broken English” or “bad English.” Jamaican Creole is looked down upon and is said to be spoken by those who are uneducated. According to Madden, “speakers of Jamaican Creole use it because their parents did and sometimes, they are unable to advance in their education,” so to a certain extent, Jamaican Creole prevents some of these speakers from experiencing upward social mobility. Nevertheless, the use of the language at home and in other informal social interactions reinforces familiarity and solidarity among its speakers. There are standards in Jamaican society of when and where Jamaican Creole is used; children learn this very quickly in order to prevent social embarrassment. According to Madden, the two times when it is entirely acceptable to speak Jamaican Creole is during songs/ folklores, and some written literature.

Jamaican Creole in Literature

Jamaican Literature started from oral storytelling. This storytelling consisted of folktales told by slaves during the colonial period and political conflicts. Through literature, Jamaicans were forging their own cultural identity, even though this literature used European literary conventions. Folk literature was the soul of the nation and people. According to Rosenberg, during the 19th century, people who were writing literature were a part of a broader movement that would legitimize a particular color, ethnic, and class group. This shifted in the 20th century in Jamaica, where many placed a priority on the formation of a national literary identity. A few Jamaican writers who use Jamaican Creole in their work are Thomas MacDermot (poet), Marlon James (writer), Claude McKay (writer and poet), Louise “Miss Lou” Bennett-Coverley (poet), and Mutabaruka (poet).

The following is a poem in Jamaican Creole by Louise Bennett-Coverley:

Nuh Lickle Twank

Me glad fi see yuh come back, bwoy,

But lawd, yuh let me dung

Me shame a yuh so till all a

Me proudness drop a grung.

Yuh mean yuh go dah Merica

An spen six whole mont deh,

An come back not a piece better

Dan how yuh did go weh?

Bwoy, yuh no shame? Is so yuh come?

After yuh tan so lang!

Not even lickle language, bwoy?

Not even lickle twang?

An yuh sister what work ongle

One week wid Merican

She talk so nice now dat we have

De jooce fi understan?

Bwoy, yuh couldn improve yuhself!

An yuh get so much pay?

Yuh spen six mont a foreign, an

Come back ugly same way?

Not even a drapes trousiz, or

A pass de riddim coat?

Bwoy, not even a gole teet or

A gole chain roun yuh troat?

Suppose me laas me pass go introjooce

Yuh to a stranger

As me lamented son what lately

Come from Merica!

Dem hooda laugh after me, bwoy!

Me couldn tell dem so!

Dem hooda seh me lie, yuh wasa

Spen time back a Mocho!

No back-answer me, bwoy – yuh talk

Too bad! Shet up yuh mout!

Ah doan know how yuh an yuh puppa

Gwine to meck it out.

Ef yuh waan please him, meck him tink

Yuh bring back someting new.

Yuh always call him ‘Pa’ – dis evenin

When him comes seh ‘Poo’.

The following is a performance by Mutabaruka of his poem which was written in Jamaican Creole entitled “Dis Poem”:

Jamaican Creole for Children

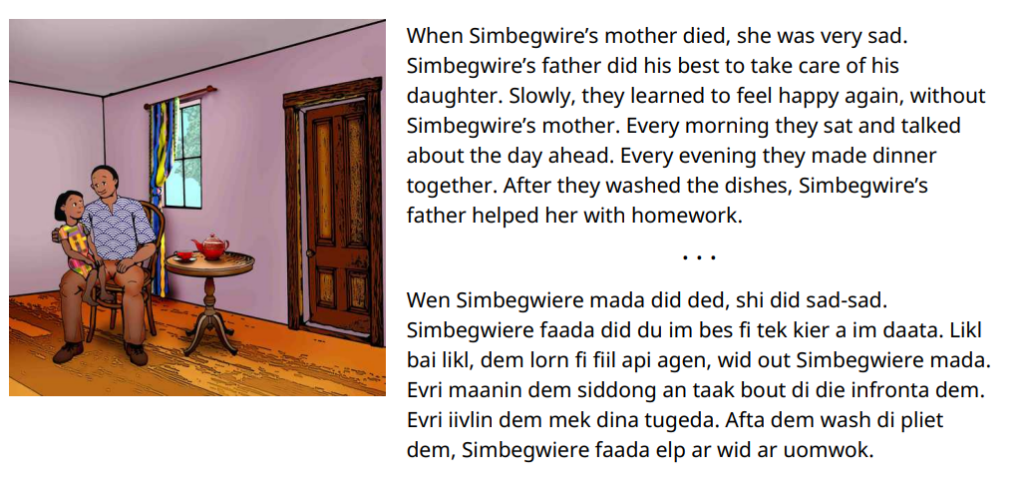

As previously mentioned, Children were taught when and how to speak Jamaican Creole. There is still stigma against using this language, due to negative views and people assuming beliefs. An example of how a child would learn Jamaican Creole, is through short stories written in Jamaican Patois. An example is provided on the online website Storybooks Jamaica which is a website for teachers, parents, and community members that aims to promote bilingualism and multilingualism in Jamaica. Through the association African Storybooks, this website has repurposed books to be in Jamaican Creole and other languages such as English and Spanish. The difficulty of the forty readings on the website go from level 1 to level 5 being the most difficult. Below an example is provided of the first page in the level 5 short story ,Simbegwire by Rukia Nantale.

Jamaican Creole in Music

Reggae is a genre of music that predominantly uses Jamaican Creole. Herbold states that “Reggae music speaks to society and communicates many political and religious beliefs of Rastafari. Whether you are captured by the beat of the music or the lyrics, the music pulls you in until you are forced to try and understand what actually is going on behind the music. Reggae musicians may use the symbolism and power of the word, such as metaphors, to instigate movement. For instance, Rastafarians consider ‘Babylon’ ‘the corrupt establishment of the ‘system,’ Church, State, and the police.” In addition, reggae music uses biblical references such as Jehovah who is the Rastafarian God. “Jah,” which is the short for Jehovah, symbolizes love, power, goodness, and protection. A popular reggae musician is Bob Marley, who used his music to express concerns about poverty, and other social injustices.

References

Herbold, Stacey . “THE DREAD LIBRARY.” Jamaican Patois and the Power of, debate.uvm.edu/dreadlibrary/herbold.html.

Madden, Ruby. “The Historical and Culture Aspects of Jamaican Patois.” Debate Central – Since 1994, debate.uvm.edu/dreadlibrary/Madden.htm.

Rosenberg, Leah. Nationalism and the formation of Caribbean literature. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.